On Sunday, 23 education thought leaders convened in Melbourne for a three-day conference to share their research, and insights, into educational leadership and how it can be improved.

The Research Conference 2017 – which concludes today – was run by the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) and included keynote speakers such as Professors Geoff Masters AO, Amanda Datnow and Toby Greany.

Another one of the speakers was Professor Chris Sarra, a former principal and nationally recognised Australian educationalist of Italian and Aboriginal heritage.

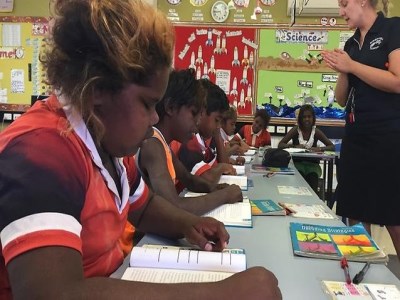

Sarra is the founder and chairman of the Stronger Smarter Institute – a non-profit organisation delivering better outcomes for Indigenous, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children across Australia.

Sarra addressed the conference about the impact of educational leadership research – for better and worse – on developing and sustaining school improvement approaches that address the profound complexities of Indigenous education.

“I wanted to challenge education researchers to contemplate research that will enhance the practice of educators in schools, rather than get in the way of it,” he told The Educator.

“Principals and school leaders are equipped to deal with these issues, but one of the challenges is that we don’t actually believe we’re readily equipped to deal with the challenges we face in Indigenous education.”

Sarra said this is because educators often get “spooked” by the difference of Indigenous children to the extent that “they forget that they’re learners in our schools just like every other learner”.

“It’s like we have a contaminated insight into the capacity of Indigenous students matched by a contaminated insight into our own ability to deliver quality education to Indigenous students,” he said.

“In the same way that we say to Indigenous students that they have to believe positively in themselves and their ability, we have to say to ourselves as educators that we have to believe positively in our ability to deliver the best for Indigenous students in our schools.”

Sarra said that as expectations in schools change, gradual progress is being made in recognising the underlying issues that impact Indigenous education outcomes.

However, he says the morale of teachers and the belief in Indigenous students as high-capacity learners has been “eroded by clumsy government policy” and investment in the pursuit of “silver bullet solutions that don’t exist”.

Direct Instruction ‘a wasteful off-the-shelf program’

Sarra spent almost seven years as principal of the Aboriginal community school of Cherbourg, located in South East Queensland, which he said faced “some dramatically complex challenges”.

“In spite of this we knew the importance of having high teacher morale and embracing Aboriginal children as if they were intelligent rather than as if they all were cognitively impaired,” he said.

Real attendance at the school rose to 94% from 62%, while Year 7 reading improved by more than 80% within five years.

“These are just some among many of the great improvement stats. In my 30 years as an educator, with many years actually working in schools and classrooms rather than just visiting and observing them, I have come to know a lot about what works and what doesn’t,” he said.

One practice that is not working, says Sarra, is direct instruction, which he described as “roaming the education debate, looking for which jurisdiction will be its next victim and trashing the morale of many Australian teachers”.

“I hope the Australia Institute and other education researchers understand the profoundly important difference between this and direct instruction that Hattie’s research referred to,” he said.

“Yes there are challenges in our classrooms across Australia and in many schools and communities. With hard work, quality teachers, quality learning programs, and high expectations relationships, we have transcended these challenges in many places.”