The latest NAPLAN data reveals a further decline in the proportion of students meeting the National Minimum Standard (NMS) in writing, suggesting a rethink is needed on how schools are working to improve students’ literacy.

Some experts warn that this writing slump can have a far greater impact, not just on students’ academic outcomes, but also on their mental health.

Jenny Atkinson is the CEO and founder of the Littlescribe online literacy program, which helps improve students’ writing skills by allowing them to create and author original handwritten and self-illustrated books.

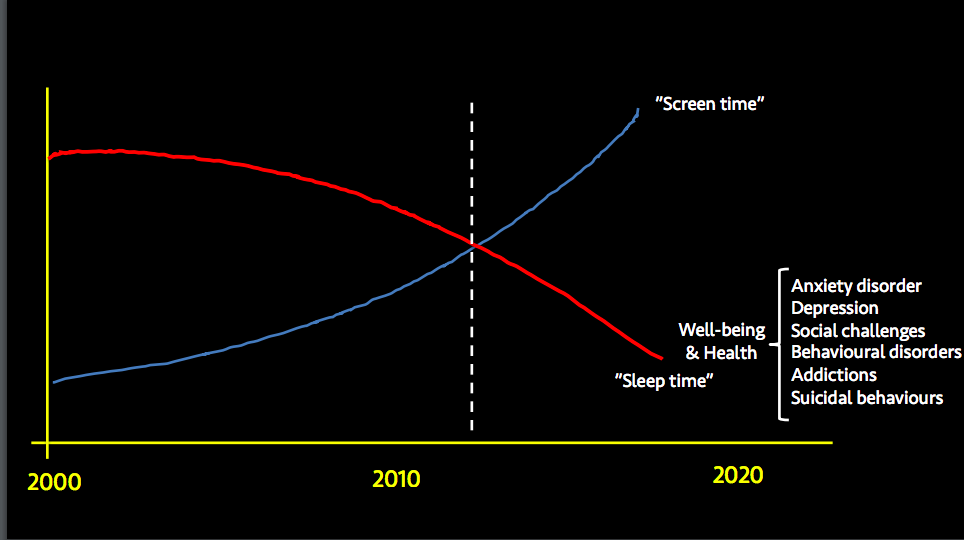

She says screen time is having a negative impact on students’ mental health and pointed to a slide (below) presented by Pasi Sahlberg which showed the relationship between the increase of screen time and a decrease in students’ wellbeing.

“The year 2011 marked a crucial impact point. Interestingly, Australian children's ability to write has decreased over the same eight-year period using NAPLAN data,” Atkinson told The Educator.

To combat this, she says, a greater focus on handwriting and drawing – not just typing – is needed.

“Handwriting and drawing bypasses our conscious and goes straight into our subconscious where many of our attitudes, beliefs and values come from and that's what drives our behaviour,” she explained.

‘Technology can interrupt the learning zone’

Atkinson said research shows that in highly stressed environments, people change their language.

“This may be a key early indicator of stress and is believed to be a better indicator than self-reported stress. It shows a relationship between personal expression and the body under stress,” she said.

“When stressed we are less likely to write ‘they’ or ‘their’ rather than ‘mine’, ‘me’ and ‘I’ more often, as we are more self-absorbed.”

Atkinson said handwriting also allows the mind to wander in a unique way for longer uninterrupted periods.

“Being in the zone, where time escapes us, is when purpose and deep thought connects, we associate this with a feeling of wellbeing. Technology with auto correct, copy and paste and messages, interrupts our zone,” she said.

“The biggest impact technology plays on wellbeing and writing is play. Play is a creative time for children to explore, experiment and expand. It is free of perfection and the need for outcomes to be achieved.”

Atkinson said incorporating interactive activities in the classroom “leaves room” for student engagement.

“In Littlescribe we have created writing projects that are seen as playful by students, such as, posters, cards and calendars,” she said.

“We've seen how giving students freedom to be creative with their writing reduces anxiety and increases engagement. Consider playgrounds with blackboards, available for comic strips to be created by students. Each day a new evolving collaborative story.”

Students perform better when phones are out of sight

Atkinson said drawing and handwriting are critical learning tools, often not explained and appreciated by students.

“It is a clever use of ‘human technology’”, she said.

“The active process of drawing and writing creates deep muscle memory, increases comprehension and the likelihood of recall. It is a personal coding system that is highly effective.”

Atkinson said that watching technology is a passive process and does not trigger as many neural pathways.

She pointed to research which found the action of drawing pushes a student to recreate new knowledge in a way that makes sense to them. The study, titled: 'The Surprisingly Powerful Influence of Drawing on Memory', explored whether drawing to-be-learned information enhanced memory and found it to be a reliable, replicable means of boosting performance.

The researchers found this technique can be applied to enhance learning of individual words and pictures as well as textbook definitions.

“Another study, from UCLA, also shows handwriting to be a more effective note taking system than typing for recall under test conditions. This is a key point I make to students in high schools,” she said.

Atkinson said the hot topic ‘technology is a distraction” generally suggests a text or pop up message interrupts the learning environment.

“I’m fascinated recent research has brought to life the expression ‘out of sight out of mind’. This is not part of the conversation and absolutely needs to be added,” she said.

“The fact is a phone turned off and, in plain sight is equally disruptive it's called a ‘brain-drain’. The brain remains turned on, waiting for the disruption and as a result reduces students' cognitive performance.”

In short, Atkinson says, participants perform better when their phone is out of sight.

“Human technology is highly effective when used well,” she said.