by Katharyn Cullen

Reading between the lines is something that our students simply can’t do. In an age of “fake news” and a year of unprecedented disaster, teaching children to make inferences is surely the least we can do.

Curriculum reform

This month, the NSW Government announced a curriculum reform advising a ‘back to basics’ approach to Literacy and Numeracy. The Curriculum Reform, led by Professor Geoff Masters, stipulated that this is due to ‘there being no significant improvement in reading levels in secondary schools since 2008 (NAPLAN)” and “a significant decline in 15 year olds’ abilities in reading since 2000 (PISA). Moreover, PISA assessments conducted between 2000 and 2018 indicate a significant longer-term and continuing decline in 15 year olds’ understandings of how to apply basic reading, mathematical and scientific knowledge and skills in practical situations (NSW Curriculum Reform, 2020).

Literacy is one of the cornerstone skills of schooling for young Australians (Daffern & Mackenzie, 2020) and as the term literacy means ‘the ability to read and write,’ it must be concerned with every curriculum area and discipline. Included in this is the ability to gain meaning from text. The fall in our PISA and NAPLAN results is a reflection of our students’ inability to comprehend texts, make inferences from what they read and adequately apply this knowledge to new situations.

Reading between the lines

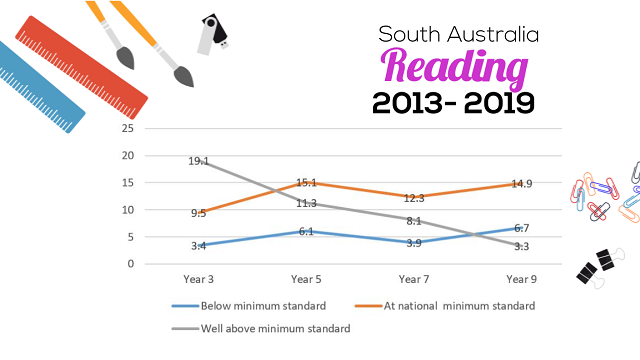

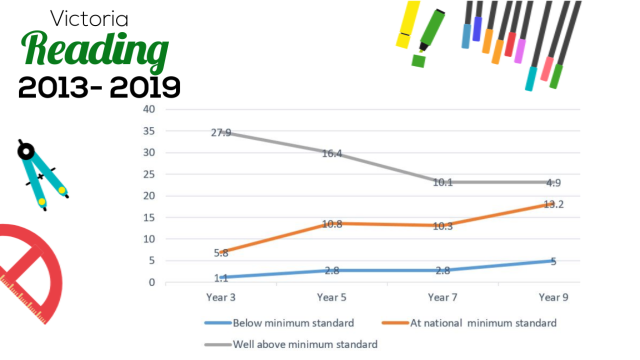

Professor Masters also records that, ‘there has been a statistically significant improvement in reading levels in primary schools since 2008 (NAPLAN), but upon closer inspection, this really isn’t the case for anyone other than our core students. The amount of students achieving ‘at national minimum standard’ from Year 3- Year 5 might be improving, but if we read between the lines, it is only because our top achievers are failing to reach their potential. This is evident in the diagrams below. Not only are the number of top performers diminishing, but the number of students ‘below minimum standard’ are increasing.

Giving students the instruction they deserve

Grattan Institute’s School Education Program Director Peter Goss identified that, “it is the transition from primary to secondary school where reading progress really begins to slow down, although we don’t really know why.” In an effort to “find the culprit”, Goss suggested that a number of students end up reading less due to technology but noted that these potential reasons do not explain the drop in Year 5-7 students’ reading progress.

Let’s be clear, technology is not the issue, neither are the students.

It has been suggested that motivation is a factor of our decline, suggesting that Year 3 students may be more compliant and make more effort than older students who may see less value in such testing schemes (Daffern & Mackenzie, 2020). Moats (2017) agrees that exposure to books and motivation to read are not enough for many students to learn to read effectively. Biological factors as well as environmental conditions such as parents reading to their child are deemed encouraging, but this does not replace the need for children to be taught how to read. Moats (2017) posits that students must be taught how spoken and written language work so that they have the tools to decipher the written word.

According to Graham (2019), many students are not receiving the instruction that they need or deserve. Teachers need a deep knowledge in the areas of language, pedagogy and the specific children the teach. They need to be confident in using metalanguage (Oakley, 2018) as without adequate knowledge, teachers will not be able to help students talk about language or explain it clearly to them (Oakley, 2018). Unfortunately, several studies have indicated that teachers may have gaps in their knowledge about language (Carreker, 2010) so, is it any wonder that we have a national literacy crisis?

Learning about words and word parts

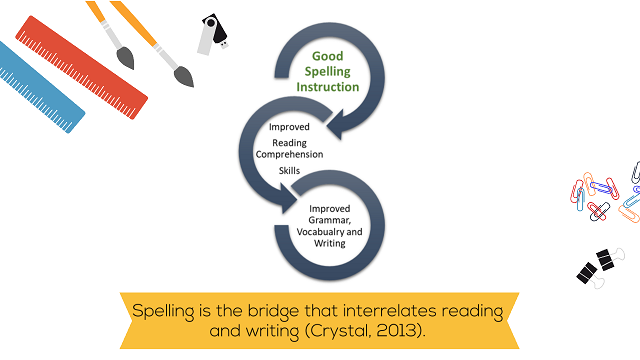

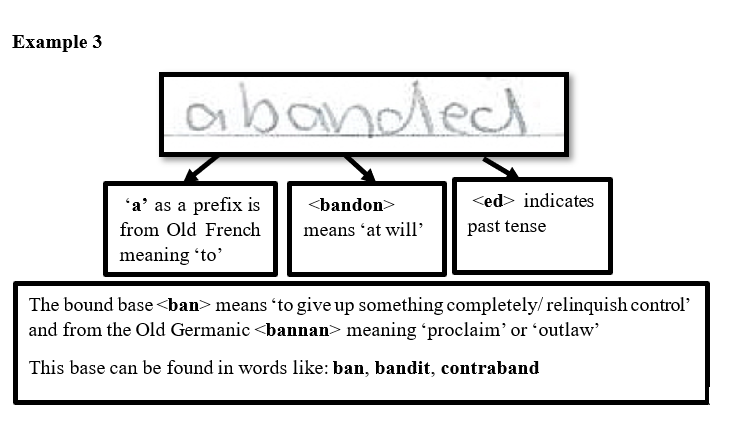

When children learn about words and word parts, this knowledge can transfer to reading (Moats, 2005). Unfortunately, unpacking vocabulary is often confined to teaching spelling skills, rather than seen as an instructional approach which should be embedded across all areas of the curriculum. Spelling is a key element of meaning- making and should bridge idea generation and text generation (Abott, Berninger & Fayol, 2010). A focus on good spelling instruction involves unpacking vocabulary and teaching students about the meanings of words. This will ultimately improve their receptive and expressive vocabulary (Rosenthal & Ehri, 2008). By understanding how words are made, students’ vocabulary will increase, which in turn improves their comprehension of new words when reading, and enables a broader range of appropriate words in their written compositions (Adoniou, 2017).

What does this look like?

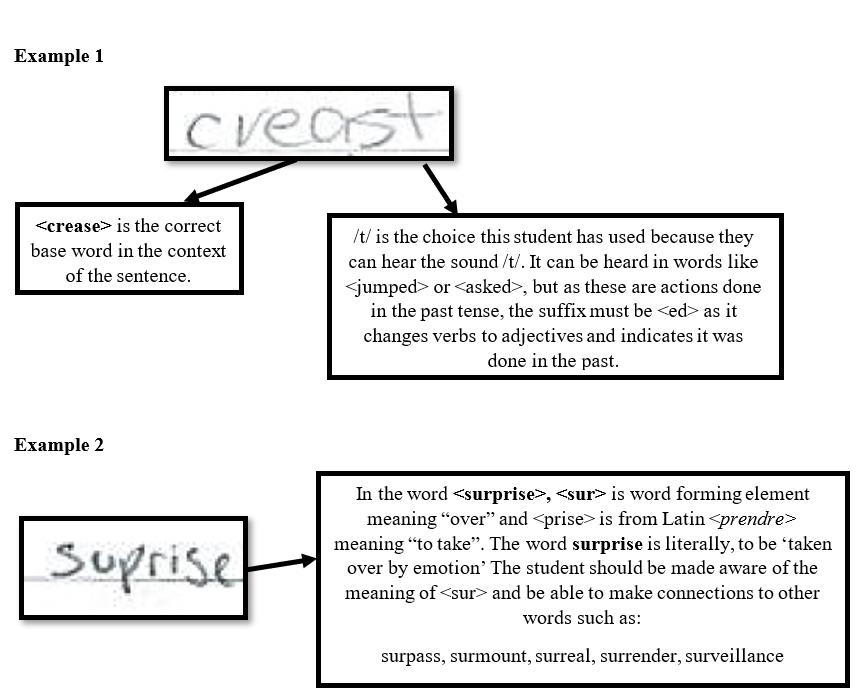

These are spelling errors taken from Year 9 written responses to the 2019 NAPLAN stimulus The Message. To unpack these spelling errors, teachers need to identify the reason for the choices the students are making. Do the words make sense within the context of the sentence? Do they have the correct tense?

Is the spelling choice plausible for the sounds the student hears in the word? Do they have the correct base word? Are they having trouble adding prefixes or suffixes?

Let’s ensure that teachers can correctly analyse spelling errors through a linguistic lens. This can then lead to conversations about other words which share the same base or root. This will increase students’ vocabulary and lead to greater reading comprehension as students will approach unfamiliar words in parts.

Spelling: It matters in high school

I have spoken to many high school teachers who think that spelling is not important in the context of their classroom. The importance of teaching spelling has been too easily dismissed with reasons such as, “they have spell-check” or “their essays are written on their computers” and “if we focus on spelling, what about everything else we have to cover like cohesion, audience and structure?”

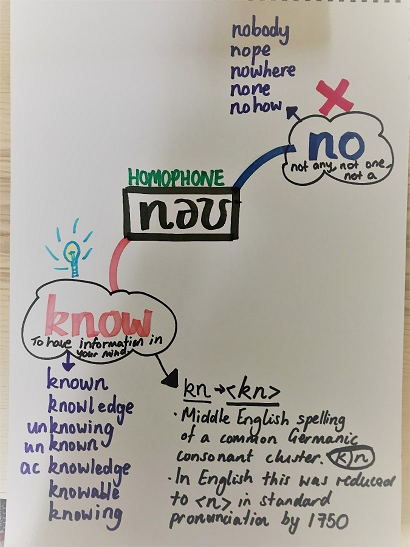

We know that spell-checker may create a word that was unintended by the writer, which in turn, changes the meaning (Scotte- Dune, 2017) of what they were trying to say. Being able to explain the difference between the homophone <no> and <know>, is a simple yet effective example of how the history of the word influences its spelling. All teachers should ask themselves, “can I confidently unpack an error like this when it appears in my student’s writing?”

Too often, writing does not reflect the ideas students might have in their head or showcase their actual thought, which ultimately leads students to underperform and teachers to misunderstand their ability. Being able to spell needs to be considered as a prerequisite to expressing vocabulary in writing (Sumner et. al, 2016) and developing deep comprehension in reading.

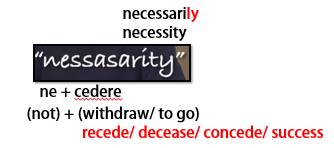

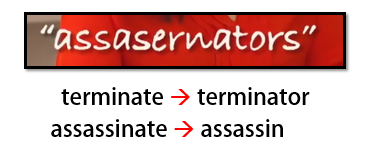

On last year’s ABC Four Corners show ‘Digi-Kids’ which explored ‘Why too many young Australians are struggling with literacy in the digital age,’ a high school teacher was unpacking spelling errors which a Year 11 student had used in an essay on Macbeth. The words <nessasarity>, <assasernators> and <desperitness> were examined as “made up words” by the student.

When are we going to place the onus on the teacher, rather than the student, when spelling errors are made?

In the word <nessasarity>, I see a two approaches to unpack this spelling error with the student. I see a student who is unsure of the difference in meaning between <necessarily> and <necessity>, or maybe isn’t aware that these are two separate words. Maybe this student hasn’t heard them articulated correctly and is unsure of their pronunciation. Secondly, if I look at this student’s spelling, I see they are not aware the reasons for the spelling. In the words <necessary>, <necessarily> and <necessity>, the <ne-> word forming element, means ‘not’, and the root word <cedere> means ‘to go’. The <c-e-d-e-r-e> root can be found in related words like recede, decease, concede and success.

After the explicit unpacking of word parts, guided by their teacher, this student would be able to understand the reason for the ‘c’ in necessary and also understand why they were confused about the pronunciation of familiar words. This student is not making up words, they are just learning, and they needed it spelled out for them (pardon the pun).

The other “made up” example, <assassernators>, seems quite obvious to me. If the base word <terminate> becomes <terminators>, then why doesn’t the word <assassinate> become <assasinators>? Why does this logic not apply? That discussion would be incredibly rich and would take the student on a journey into the logic of the English language.

Spelling is a unique skill which, when taught explicitly, leads to an improved understanding of vocabulary. This assists with reading comprehension and gives students an enriched capability to write with a deeper understanding of grammar and punctuation. Spelling is the bridge that interrelates reading and writing (Crystal, 2013) and is where our focus must be placed to improve the literacy results of this country.

Katharyn Cullen is the Assistant Head of Junior School at Seymour College in Adelaide with research and teaching interests in language and literacy education. Katharyn regularly engages as a literacy education consultant and conference speaker and is currently completing a PhD at Torrens University, with a specific research focus on spelling.