Only 22% of family members and carers of students with a disability agreed they had received adequate educational support during the pandemic.

Many respondents in our new research, and survey, on behalf of Children and Young People with Disability Australia (CYDA) reported being forgotten in the shift to remote learning, or being the last group to be considered after arrangements had been made for the rest of the class.

A number of parents and carers said the pandemic period gave them an insight into the level their child was working at. This occasionally came as a surprise, as parents discovered with adequate support their child could complete work at a much higher level than the school had recorded.

For others, this period illustrated how little progress their child had been making and the lack of support they were receiving at school. Several respondents said they were considering changing schools or home schooling their children as a result.

Still left behind

Our survey was launched on April 28, 2020 and remained open until the June 14, 2020 (nearly seven weeks). It asked questions on the experiences of students with disabilities and their families when schools across Australia had mostly closed.

It also covered the period of transition back to face-to-face teaching for the majority of students.

We received more than 700 responses and 1,145 text comments. The responses mainly came from family members of children with disability. Around 5% of respondents were students with disability, and of those most were high school or university age.

Nearly 80% of respondents said responsibility for education shifted from teachers and schools and onto parents during the survey period.

More than half of respondents said the curriculum and learning materials didn’t come in accessible formats. Parents reported having to do significant work to translate learning materials into a useful format for their children.

Some reported receiving exactly the same materials and support as those provided to students without disability, with the onus entirely on parents to make the necessary adjustments.

This caused some family members to feel they were letting students with disability down because they did not have the skills required to adjust the materials appropriately.

One young person said: "Only one special education teacher was modifying learning material and in regular contact and encouragement from the special education department in high school".

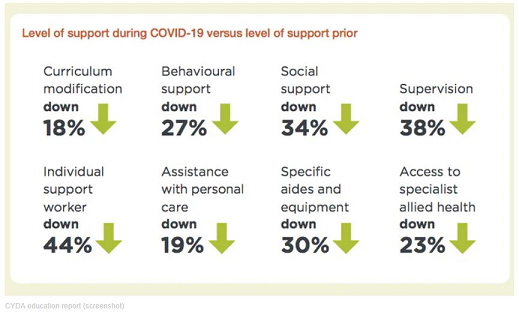

Some children were unable to engage online and so missed out on being part of a learning community. Others felt schools had not done enough to facilitate access to this. Many respondents said the usual supports they received dropped off, most notably in terms of supervision, social supports and individual support workers.

Nearly three quarters of respondents said students with disability felt socially isolated from their peers. Many said this and other consequences of the pandemic were having a significant impact on their mental health.

Just over half of respondents indicated a negative impact on the mental health and well-being on either themselves or the child or young person with disability under their care.

Cracks in the system

Some families used funding from the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) to help support remote learning. They redeployed support workers from personal care into helping children engage in learning, risking they may not have enough support worker hours left at the end of their plans.

Others had requests for more funding turned down by the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) on the basis education supports should be covered through mainstream services. Overall there was a lack of clarity about how the NDIS could be used to support remote learning.

As one parent reported:

“I was lucky enough to have had funding to support in-home supports, which I used to assist with schooling during COVID-19. I am the sole parent of two children with disability, plus an essential worker. Without this support my children would have received no quality schooling at all during the school-closures”.

Others felt the support was no worse during the pandemic, but this was mostly because they had not been well supported beforehand. Where support had been received, it was often in response to advocacy work done by parents who had contacted schools (sometimes repeatedly) and requested the materials and adjustments their children required.

What have we learnt?

We found children who received one form of support were 24% more likely to feel part of a learning community and 36% more likely to say they received adequate support in their education.

And the more support received, the better. For those who received two or more types of support, they or their parents were

- 88% more likely to say they felt part of a learning community

- more than twice as likely to report adequate support in their education

- 48% more likely to say report engagement in their learning

- 18% less likely to report feelings of social isolation.

Social supports had the strongest association with students feeling supported, part of a learning community, engaged in learning and feeling less socially isolated.

Our research shows that, with careful planning and effort by education systems and teachers, students with disability can thrive through the pandemic.

But the support should

- ensure students are made to feel part of a learning community through connecting them with their peers

- ensure learning materials are accessible and specific to the needs of students

- teachers provide reasonable supports in partnership with children and families – it should not be left to families or students to navigate

- ensure the support from the NDIS and the education system are complementary.

This article was originally published in The Conversation by Helen Dickinson, Professor, Public Service Research, UNSW; Catherine Smith, Lecturer, University of Melbourne and Sophie Yates, Postdoctoral Fellow, UNSW.