A record number of Australian principals are struggling with violent assaults, teacher shortages and serious mental health concerns, the the latest national survey of the profession’s health and wellbeing reveals.

The Australian Catholic University’s (ACU) annual Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey 2022 found school leaders are working an average of 56 hours a week under the toughest conditions they’ve seen since the survey started 12 years ago.

An alarming 47.8% of principals triggered "red flag" alerts (generated when school leaders are at risk of self-harm, occupational health problems or serious impact on their quality of life) – a staggering 64% increase from 2022.

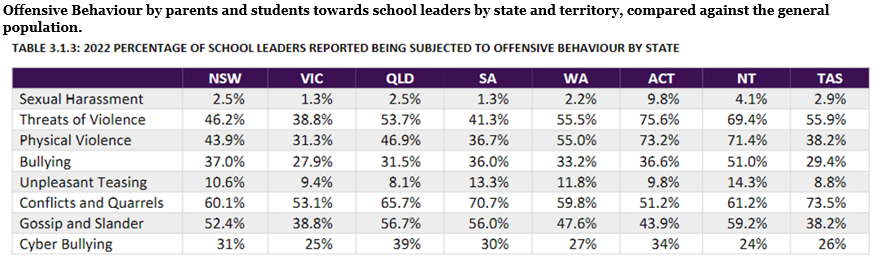

ACT principals reported the highest rate of red flag alerts (58.5%) and physical violence and/or threats from students (80.5%). The alarming finding follows a discussion paper released in January 2023 that warned the Territory’s leaders were feeling overwhelmed by “crushing workloads”, “frequent abuse” and “a culture of fear”.

Worryingly, principals in the Northern Territory (57.4%), New South Wales (55.7%) and Western Australia (52.2%) generated a similar number of red flag alerts to their ACT counterparts, suggesting the crisis is national in scale.

By sector, special school principals triggered the greatest number of alerts (56.3%), followed by those in public schools (51.8), Catholic schools (35.3%) and private schools (27.7%).

According to the demographic breakdown of make and female leaders, the percentages were found to be higher for female principals across all school sectors in Australia.

“Women school leaders tend to work longer hours than men, and report higher job demands,” World leading educational psychologist and co-lead investigator Professor Herb Marsh, of ACU’s Institute for Positive Psychology in Education, told The Educator.

“Women school leaders reported poorer levels of work-life balance, presumably because they are more likely to be the primary caregiver at home.”

The survey’s co-lead, Associate Professor Theresa Dicke from the ACU’s Institute for Positive Psychology in Education, said the report’s findings are “very concerning for the profession.”

“The red flags demonstrate that our school leaders are at breaking point,” Associate Professor Dicke told The Educator. “We know there have been initiatives introduced to support principals’ health and wellbeing but unfortunately these results show they don’t go far enough.”

An alarming trajectory: Violence against principals up 63% since 2011

Physical violence against principals was high across the board, with a record 44% reporting they had been on the receiving end of an assault.

Principals were approximately 4.12 times more likely to be subjected to physical violence from students than they were from parents and care givers, while the latter were responsible for one third of all threats of violence against principals.

“If we look at the measure of physical violence committed against principals alone, the figures may not seem high year-on-year, but since 2011 when the survey started, we have seen a 63% increase,” Associate Professor Dicke said.

“And in areas offering protective factors such as job satisfaction, mutual trust between employees, meaning of work, role clarity, and commitment to the workplace, we have seen drops to the lowest levels since 2011. This means we are seeing trends growing in the wrong directions and that is incredibly concerning.”

Teacher shortages now a major cause of stress for principals

Professor Marsh said the stress caused to principals by the national shortage of teachers has been a key finding of concern this year.

“It featured as the third highest source of stress for school leaders, up from 12th the year before, and the problem shows little sign of abating,” Professor Marsh told The Educator.

“Incidents of physical violence against principals have also increased at an alarming rate. We saw a drop in physical violence during the Covid years due to remote learning and hoped this encouraging trend would continue. Instead, however, there has been an enormous jump.”

Professor Marsh said levels that are now at their highest level since we began our survey – 44% in 2022 compared to 27% in 2011.

“No one deserves to be subjected to violence at work, yet principals are increasingly in the firing line.”

‘The cracks have deepened’

‘The cracks have deepened’

Associate Professor Dicke said the cumulative pressures on principals “have now reached a point where the cracks have deepened”.

“Our longitudinal research is the only type of its kind to really put a finger on the pulse of what school leaders are feeling and how they are coping. We must now act on this research,” she said.

Associate Professor Dicke said governments, employers, associations, and school leaders themselves have a role to play in reversing the negative trends.

“We need to remove low-value tasks that are nothing more than administrative burdens, and wellbeing priorities need to be incorporated into performance frameworks. Professional associations also need to look at ways to further support their members,” she said.

“School leaders also need to be encouraged to seek the supports they need to improve their health and wellbeing. Without healthy school leaders, we cannot expect our teachers, students, and school communities to flourish.”

Overwhelmed public school principals could migrate to private sector

Professor Marsh says the recognition that private schools are better resourced and experience lower rates of occupational health and wellbeing issues may see public school leaders migrate to the sector.

“While Independent principals tend to work longer hours, particularly during school holidays, they tend to have better resources. Consequentially, they tend to have lower quantitative, cognitive, and emotional demands, lower burnout levels, and higher general health,” he noted.

“Independent school leaders also experience much less physical violence than government school leaders. As working conditions seem to be better in Independent than government schools, we might see a migration of the best government school principals to the private sector in the future.”

‘I often work a 60-plus hour week and I still don't get everything done’

Sally Buick, principal at Killester College in Springvale, Victoria, said the hours she works are “simply unsustainable”.

“I often work a 60-plus hour week and I still don't get everything done,” she told The Educator, adding the compliance and regulatory obligations principals have to meet are “ever increasing”.

Buick said principals are required to advocate for students, staff and their families “in a system that does not have capacity”.

“It is impossible to educate a young person experiencing a significant mental health crisis or one who is dealing with the impact of a parent experiencing one, nor work alongside a colleague in distress,” she said.

Buick said it has been heartbreaking to see that people who in need of help are often unable to access any support services “for months”.

“We have to step in and create opportunities and supports to manage the risk while we wait for assistance and support,” she said.

“The managing of the risk of a young person who is suicidal and who has been discharged from hospital without adequate care, causes many sleepless nights.”