A first-of-its-kind study has revealed the devastating cost of Secondary Traumatic Stress on school staff, with the research showing half experience some degree of depression and more than a third are considering leaving the education sector because of its emotional impact.

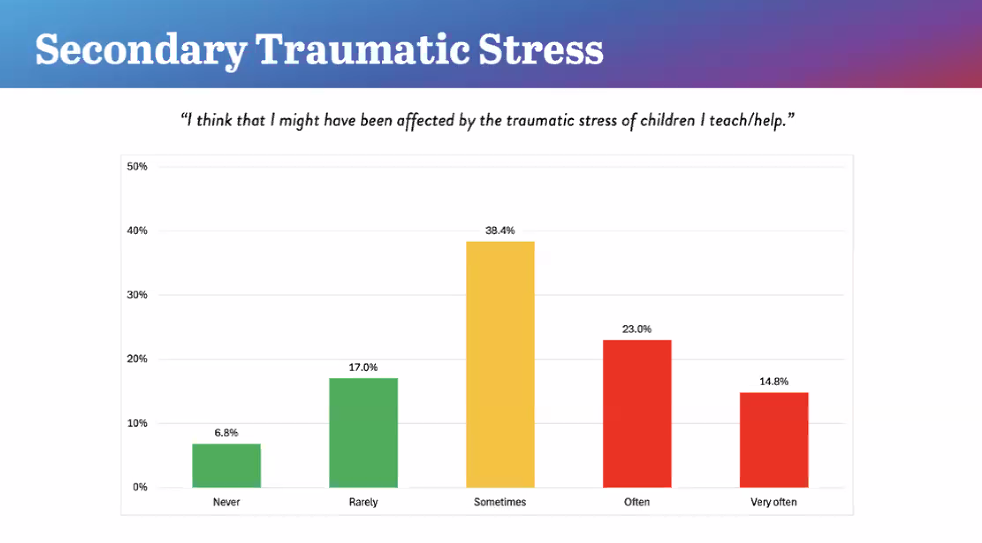

Secondary Traumatic Stress – what happens to you when you see or hear about someone else’s trauma – has been identified as a significant problem within schools, with 39% of education staff frequently affected by the trauma of others, while a further 38% say they experience it sometimes.

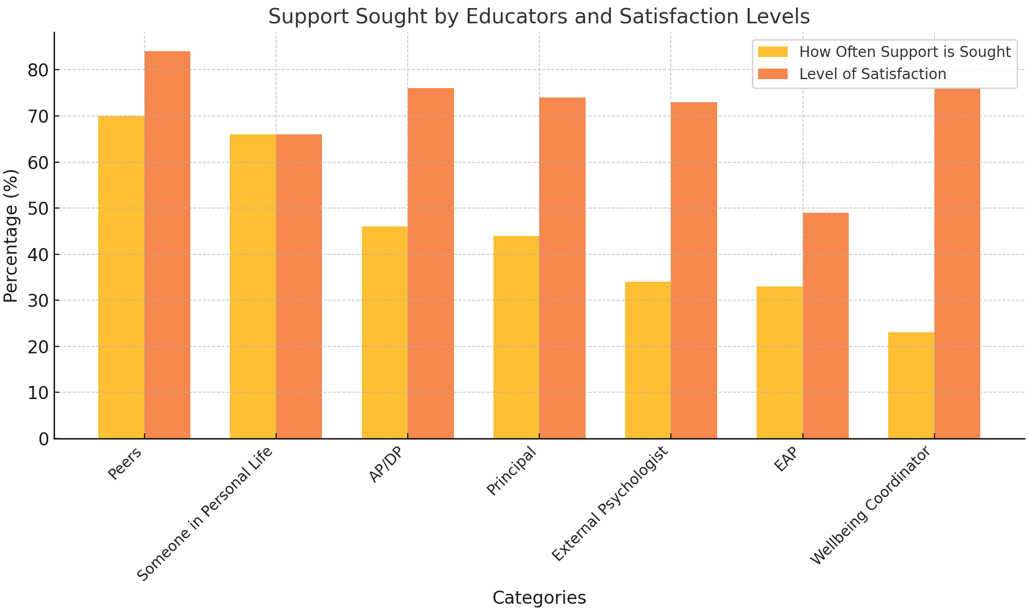

Data: Deakin University and Dr Adam Fraser

The study, conducted by Dr Adam Fraser and Dr John Molineux from Deakin University, is Australia’s first ever study on the impact of secondary trauma on school staff. The research involved nearly 2,300 participants documenting 1,068 experiences, many of them harrowing.

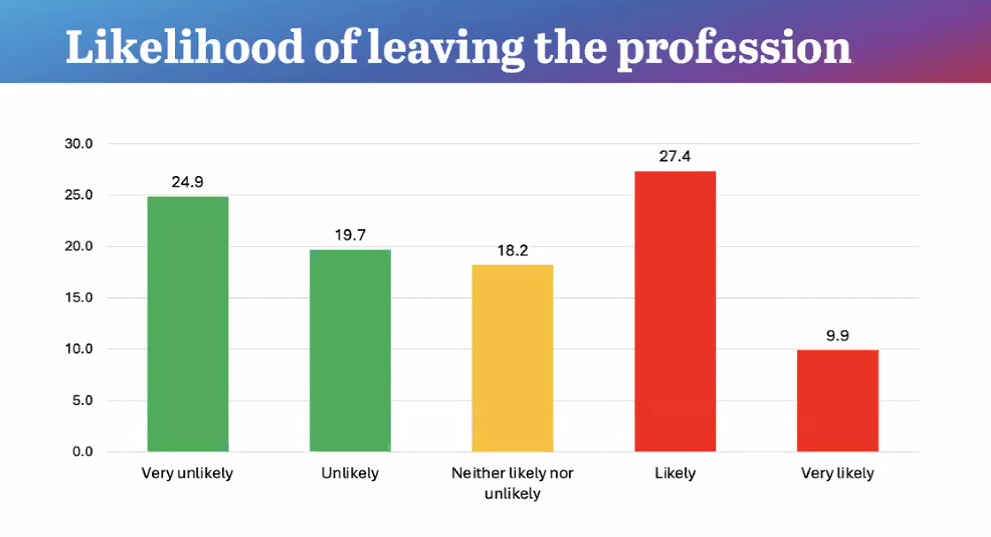

The profound impact of this trauma has caused 37% of educators to consider walking away from the job, while another 18% are undecided about staying.

Data: Deakin University and Dr Adam Fraser

One of the study’s more alarming findings was that 16% report being “often or very often depressed”, while more than half (51%) experience some degree of depression.

Educators ‘shouldering the roles of social workers’

Educators are increasingly shouldering the roles of social workers, supporting traumatised students in the absence of adequate services – often due to funding and resource shortages.

What can be done?

Dr Fraser said if the impact of STS on educators is to be alleviated, the first thing systems must do is “acknowledge that it is an actual problem and engage in the narrative.”

"Some systems did not want to engage in the discussion," Dr Fraser told The Educator. "Secondly, systems need to recognise that education has evolved dramatically; it is no longer simply about literacy and numeracy."

For many students, the school is the only stable and functional environment they ever interact with, Dr Fraser noted.

"We can no longer measure the success of a school by NAPLAN or HSC scores. For many schools, these numbers are not an accurate indication of their achievement," he said. "Also, second hand trauma combined with high workloads really drives burnout."

Dr Fraser said systems have to get serious about reducing workloads that take educators away from getting better student outcomes and have systems and processes that streamline workflow.

"Finally, support and encourage principals and staff to focus on practices that help them process and recover from secondary trauma, by giving them training that targets this very serious challenge."

Systems must prioritise resources to support educators' mental health.

Matthew Johnson, president of the Australian Special Education Principals Association, said special education environments are particularly challenging for educators, given the diverse needs of students in these settings.

He says multiple factors have exacerbated these challenges in 2024.

“These include Increased emotional and behavioural complexities in students; high staff turnover and burnout rates, which create an environment of instability for both students and educators,” Johnson told The Educator.

“Another factor is limited access to specialised mental health support for staff, leaving many educators without the necessary tools to manage their own stress effectively and limited professional development or resources focused on trauma-informed practices, which could help staff navigate the complexities of STS.”

To mitigate the impact of STS, Johnson says it’s crucial for school leaders, systems, and policymakers to recognise the signs of secondary trauma and prioritise resources to support educators' mental health.

“This can include ongoing training in trauma-informed care and self-care strategies, dedicated mental health support through counselling services, peer support networks, and stress reduction workshops,” he said.

“Workload adjustments could be made to allow staff the time and space to recuperate and process the emotional demands of their work.”

Younger educators, rural schools worst affected

Interestingly, the study indicates that secondary trauma has a more devastating impact on educators than personal trauma.

Younger educators (up to age 29) are particularly vulnerable, showing 8% experience higher burnout rates; 7% report reduced ability to cope with trauma; 20% show higher mental health risks; and 11% have a greater likelihood of turnover.

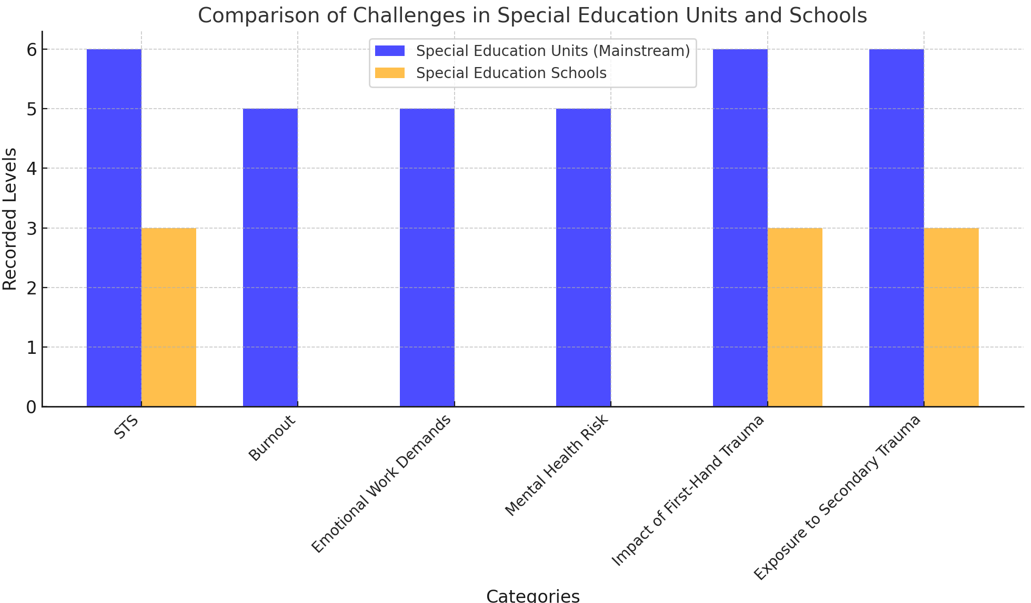

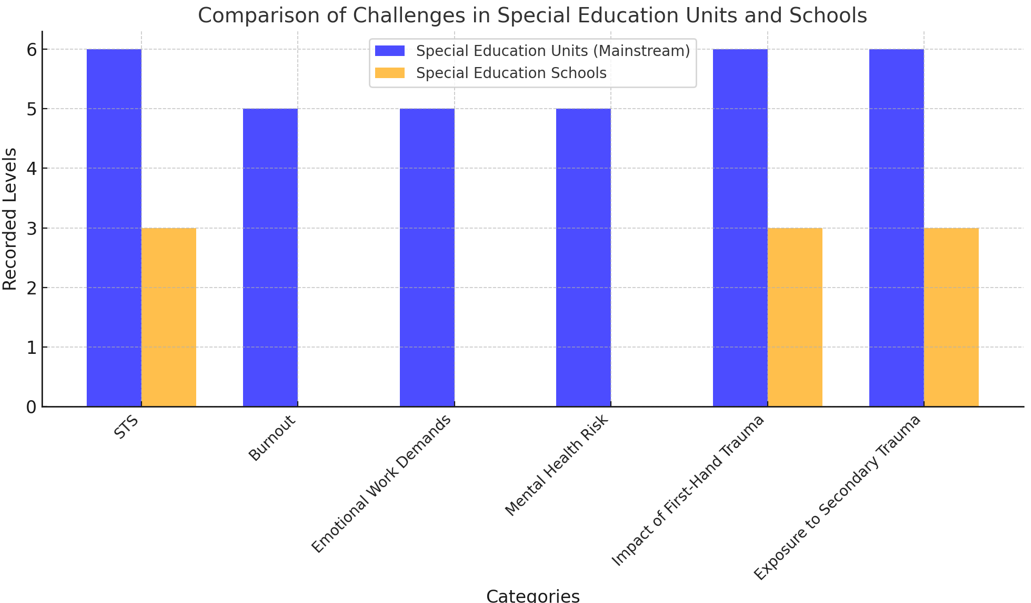

Rural and remote schools, as well as staff in Special Education units, were disproportionately affected across almost all metrics.

However, the researchers found that exposure to secondary trauma, rumination, emotional work demands, exposure to first-hand trauma, and impact of first-hand trauma all showed a pattern where they increase with an increase in experience.

“This finding suggests that there may be a cumulative effect of trauma that accumulates in educators over the years,” Dr Fraser said.

In terms of geography, the research found rural and remote schools have more challenges than the regional schools, which in turn have more challenges than metropolitan schools.

STS, burnout, emotional work demands, exposure to secondary trauma, mental health risk, rumination, emotional work demands, and risk of turnover were the highest in rural/remote schools.

“The sense is that this is happening again, and nothing is going to change,” Johnson said.

Staff forced to send kids back to unsafe homes

Many educators cited the lack of access to services for students in abusive or neglectful environments as a significant stress source. The study found staff are often forced to send students back into unsafe homes, perpetuating the trauma cycle for educators and students.

The top four sources of trauma for students were identified as domestic violence, parental neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse.

Leaders are the favoured source of support

When asked what their main source of support for strong relationships, reduced rumination, mental health risk and turnover risk, most responds said their supervisor was most helpful.

“If you have a leader who you feel safe with, and you can freely express your frustrations and concerns, it has a very positive impact on the three-outcome variables,” Dr Fraser said.

The next most effective support is from colleagues and peers, then from family.

The good news

Despite these challenges, educators remain steadfast in their commitment, with 75% saying they believe they can often or very often make a difference, and a massive 81% saying they’re proud of their efforts to help students.

Dr Fraser said the above finding is the reason why schools are handling the sometimes impossible challenges they face.

“Their dedication is so great they will literally walk through fire for the students. However this dedication leads them to push through what is reasonable,” he said.

“Also, many educators feel that systems are taking advantage of this dedication and not supporting them in a way where they can do the job and have good wellbeing at the same time.”

Johnson said this finding that most educators can often or very often make a difference “speaks to the unwavering dedication and passion of special education professionals, who consistently go above and beyond to meet the needs of their students, even in the face of adversity.”

“However, while this commitment is incredibly admirable, it also underscores the importance of recognising and supporting the well-being of these educators,” he said.

“Their belief in their ability to make a difference and their pride in their work are what keep them motivated, but we must also acknowledge that these educators are human beings, facing emotional and physical demands that are not sustainable without the proper resources and support.”

Johnson said the fact that so many educators feel proud of their work and believe they make a difference is a testament to their resilience, but it’s critical to ensure that they don't burn out in the process.

“As an association, we advocate for systems that not only recognise the emotional and psychological challenges educators face but also provide them with the support they need to continue making that difference without compromising their own mental health.”