- K/12

- Higher Education

Rising Stars 2022

Jump to winners | Jump to methodology

A new generation of teacher-leaders

Sponsored by: Only four months into 2022, one could be forgiven for wondering if a profound test of nerve has been thrust upon us. Between the global pandemic, a “once in 500 years” flood and now the dramatic reshaping of the international rules-based order following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, these converging historic events are causing great consternation for young people.

Only four months into 2022, one could be forgiven for wondering if a profound test of nerve has been thrust upon us. Between the global pandemic, a “once in 500 years” flood and now the dramatic reshaping of the international rules-based order following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, these converging historic events are causing great consternation for young people.

Mental health was a key focus of the 2022 Federal Budget, with the government announcing $9.7m for new measures to help teachers and school leaders better understand and respond to the mental health and wellbeing needs of students.

According to the World Health Organization, mental health disorders are one of the main causes of disability during adolescence. In Australia, almost a quarter of young people are psychologically stressed, yet many do not seek help.

“Principals and teachers have been magnificent in finding solutions to complex matters and are now focusing on creating an environment for their school communities that is about ‘getting back to normal”

Andrew Pierpoint, Australian Secondary Principals’ Association

“The mental health and wellbeing of Australian children and young people has been on a steady decline over the past decade, and the impact of Covid has only exacerbated this,” Dr Addie Wootten, CEO of Smiling Mind, tells The Educator.

Pointing to research from the National Child Mental Health Strategy, Dr Wootten says mental illness affects one in seven primary school-aged children, and the number rises to one in four by the time children reach the high school years.

“The social and emotional impact of the pandemic could have far-reaching impacts and there have already been reports of this broadly impacting learning outcomes with reports of students being at least 4–5 months behind due to school closures as well as significant social and emotional impacts,” she says.

Rising to the occasion

Amidst these crises, Australia’s school leaders, teachers and support staff are helping young people not just make sense of the dizzying changes they are experiencing, but also focus on their academic and social and emotional development – and while battling an increasingly complex crisis of their own.

In addition to worsening staff shortages that have brought schools in some states to a standstill, the workloads of teachers and leaders are reaching unsustainable levels. According to the latest Australian Principal Occupational Health and Wellbeing Survey – conducted by the Australian Catholic University’s Institute for Positive Psychology and Education – principals and their deputies worked on average at least 55 hours a week, while a quarter of those reported working more than 60 hours a week. Twenty-nine percent of school leaders received a “red flag” alert email, which is generated and sent to the report’s author when a principal answers ‘yes’ to a statement like ‘In the past week I’ve felt like harming myself’.

Still, just as Australia’s teachers helped students adapt to disruption, they too have been helping each other to rise above the gruelling workloads and increasingly complex changes for the greater good. Incredibly, many have shifted their focus from persevering through these crises to reimagining new ways of teaching and learning, and sharing this practice among their colleagues to create inspiring and empowering networks of educational excellence throughout their communities and beyond.

“As well as fresh approaches in teaching and learning, we are likely to see experimentation in schools with trends that are having a big impact in post-school education, such as micro-credentialling and digital passports”

Beth Blackwood, Association of Heads of Independent Schools of Australia

Preparing for the future

Andrew Pierpoint, president of the Australian Secondary Principals’ Association, says principals and teachers have been “magnificent” in finding solutions to extremely complex matters and are now focusing on creating an environment for their school communities that is about “getting back to normal”.

However, for most schools, the ‘normal’ they knew has been eclipsed in the face of new ways of teaching and learning, and there is a growing expectation that many of those changes will be here to stay.

Association of Heads of Independent Schools of Australia president, Beth Blackwood, says the rapid technological and social transformation that education has gone through means that many teachers and leaders are “working in the present while investing in the future”.

“I expect to see further innovations emerging this year in accommodating student agency and student voice – for example through self-directed learning,” Blackwood tells The Educator. “As well as fresh approaches in teaching and learning, we are likely to see experimentation in schools with trends that are having a big impact in post-school education, such as micro-credentialling and digital passports.”

Indeed, this experimentation is needed more than ever as vocational education and training and other post-school opportunities for young people appear increasingly uncertain. According to new research from Australia Institute’s Centre for Future Work, the nation’s vocational education and training system “shows growing signs of erosion, fragmentation and dysfunction”.

But this, as is the case with all crises, has presented an opportunity for educators Australia-wide to recalibrate and improve on old ways of thinking and doing.

“The silver lining of the pandemic restrictions and the pressure of rapid change was the flowering of innovation. With old assumptions cast aside, teaching teams have created some wonderful untapped resources which we can build into new and more purposeful learning designs”

Prof Elizabeth Johnson, Deakin University

From chaos to innovation

Prof Elizabeth Johnson, deputy vice-chancellor of education at Deakin University, says that with old assumptions cast aside, teaching teams have created new resources which can be built into new and more purposeful learning designs – particularly in digital learning, which is becoming increasingly important as schools seek to equip young people for the workforce of the future.

“The silver lining of the pandemic restrictions and the pressure of rapid change was the flowering of innovation,” Prof Johnson tells The Educator. “Now is the time to re-evaluate efforts to date and identify highly intentional ways to lean on technology tools – without overcomplicating or overengineering – to fuel progress in digital learning with the right frameworks to support students, academics and other stakeholders.”

Looking ahead, these opportunities to break down the archaic walls that no longer serve today’s forward-thinking leaders and teachers will only grow. Recognising this, The Educator has been showcasing the pockets of excellence that have been popping up across Australia’s education landscape in our annual Rising Stars report.

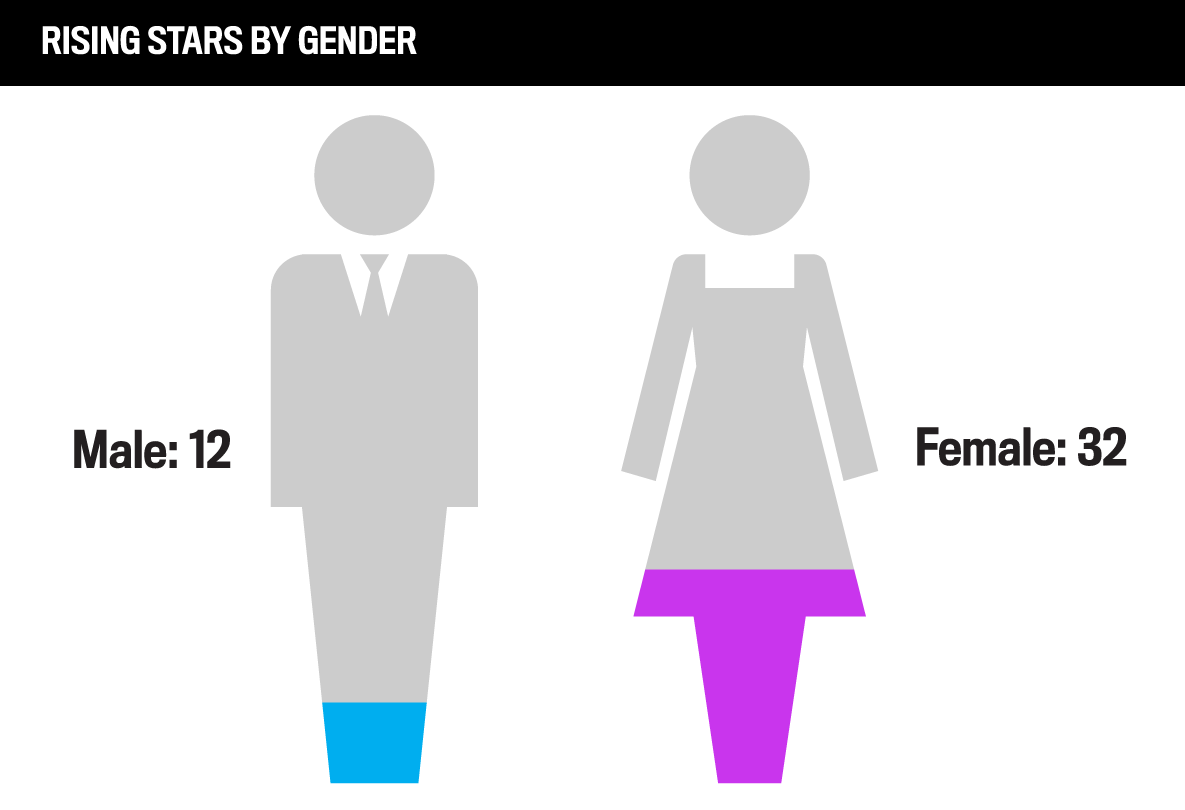

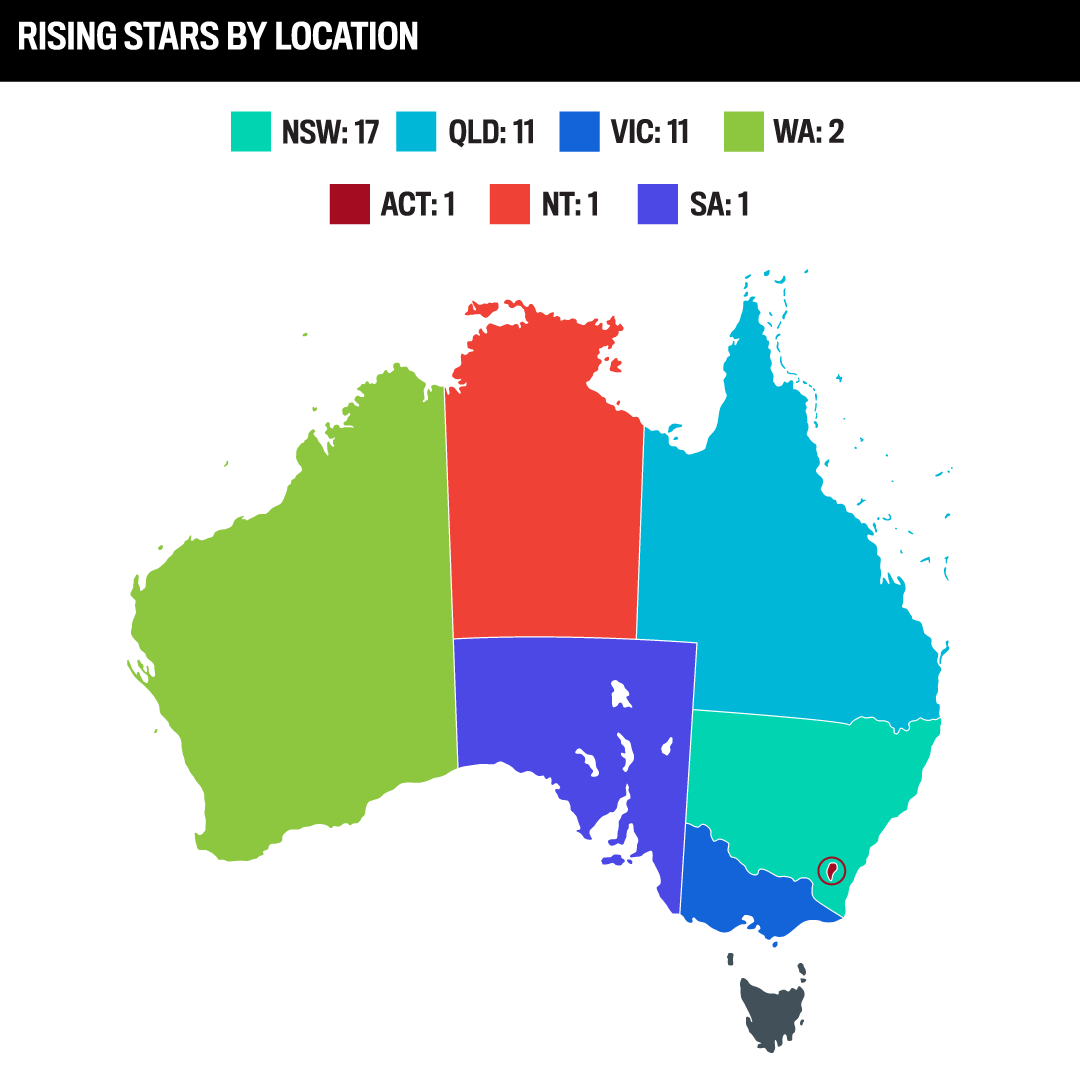

In November 2021, The Educator kicked off the latest search for the best up-and-coming talent in the education sector by asking readers to nominate emerging leaders in education who are making waves in the early stages of their career. After carefully reviewing more than 80 nominations, The Educator team selected 44 young professionals with outstanding leadership, initiative and passion, expertise, innovative approach to teaching and learning, and vision – all necessary to thrive in the ever-evolving education landscape.

Rising Stars 2022

- Alex Wharton

Head of Middle School, Carinya Christian School Gunnedah (NSW) - Amelia Farrell

Secondary English Teacher, A B Paterson College (QLD) - Ashley Keith Pratt

Executive Director, Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Innovation, Melbourne Girls Grammar - Catherine Gallus

Senior English Teacher/Literacy Learning Specialist, John Monash Science School (VIC) - Drew Mitchell

Head of Department, Support Services, Marsden State High School (QLD) - Gabe Robbie

Head of Department, Humanities and Social Sciences, Concordia Lutheran College, Toowoomba (QLD) - Echo Gu

Teacher/Student Data Analyst, Lauriston Girls’ School (VIC) - Ella Evans

Economics and Geography Teacher, Lindisfarne Anglican Grammar School (NSW) - Elle Smith

Senior Learning Coach, St Andrew’s Cathedral School (NSW) - Eliza de Hoogh

Teacher, Australian Christian College, Singleton (NSW) - Emily Brewer

English Teacher, Lindisfarne Anglican Grammar School (NSW) - Emma Enticott

English Teacher, Forest Hill College (VIC) - Harriet O’Donnell

Teacher, St Andrew’s Cathedral School (NSW) - Holly Millican

Mathematics Teacher, South Grafton High School (NSW) - Jack Pick

Teacher, Lobethal Lutheran School (SA) - Jenna Cullen

Head of Department, Teaching and Learning, Teacher Librarian, Marsden State High School (QLD) - Jennifer Frank

Head of Rolland House and Duke of Edinburgh Coordinator, St Philip’s College (NSW) - Kara Handberg

Acting Head of Senior School, O’Loughlin Catholic College (NT) - Kara Williams

Leader of Wellbeing and Junior School, Australian Christian College Singleton (NSW) - Karina Smith

Classroom Teacher, Kalianna School Bendigo (VIC) - Karinne Cooke

Junior School Coordinator (Pastoral Care and Operations), Acting Head of Junior School, St Philip’s Christian College Cessnock (NSW) - Lachlan McGinness

Senior Physics Teacher, Canberra Girls Grammar School (ACT) - Lauren Holding

Head Teacher, Instructional Practice, NSW Department of Education - West Wallsend High School (NSW) - Liam Bassett

Director of Digital Learning, Westbourne Grammar School (VIC) - Lucy Loxton

English Teacher, Presbyterian Ladies’ College, Perth (WA) - Markus Munday

Campus Year 1 Teacher, Scots College (previously Beaconhills College Pakenham) (NSW) - Matthew Hawke

Year 6 Teacher and Wellbeing Leader, Knox Grammar Preparatory School (NSW) - Mitchell Mills

Acting Head of Year, Head of House and Senior Physical Education Teacher, Saint Stephen’s College (QLD) - Rebecca Newman

Acting Grade 2 Leader, St Andrew’s Cathedral School (NSW) - Samuel Dudley

Teacher, Ormiston College (QLD) - Scott Waring

Head Teacher, Secondary Studies, Great Lakes College Senior Campus (NSW) - Sophie Sharp

Year 1 Teacher, Tarrington Lutheran School (VIC) - Steffany Mylonas

Senior School Teacher, Redeemer Lutheran College (QLD) - Stephanie Browning

Head of Curriculum, Response to Intervention, Southport State High Independent Public School (QLD) - Tabitha Southey

PE and Health Teacher, Canterbury Girls’ Secondary College (VIC)

Methodology

The Rising Stars 2022 report was launched with a call for entries to the entire Australian K–12 education sector. To be eligible, candidates must be aged 35 or under, must be working in a role related to the K–12 education sector, and must be able to demonstrate effective leadership, innovation and achievement in their career to date. Both self-nominations and nominations on behalf of colleagues are accepted.

The winners were judged by the substance of their nominations; namely, nominations that illustrated specific outcomes that were achieved and the relevant data to support their claims. The Educator team carefully reviewed each nomination, examining how each individual had made a meaningful and tangible difference to teaching and learning outcomes in their schools. This could include data on improvements across key areas such as students’ in-class engagement, academic achievement, attendance and wellbeing.